Against Enormous Odds, an Activist Fights Fracking in His Hometown

In many ways Williamsport, Pa., (pop. 29,304) is the perfect American city. Nestled into a river valley, it’s the town where Little League was born. The local high school team is called the Millionaires, harkening back to the days when Williamsport boasted numerous wealthy elites as citizens. Mountains provide a stunning backdrop to the city’s stone buildings, and American flags fly everywhere. Williamsport is the type of place where you get confused about what year it is, until someone in a new car talking on an iPhone pulls alongside you. It’s wonderful.

But in 2008 Williamsport was in terminal decline and had been for years. Like countless other former boomtowns, its residents had trickled away in search of better opportunities, and the town was shrinking.

After years of living just down the river from Williamsport, skinning his knees on its playgrounds and going to concerts at its church fellowship halls, DJ Robinson moved to Philadelphia.

In 2009, Robinson returned to visit his family for the holidays and noticed things had changed in the place he called home. People were buzzing. New faces populated his old haunts. Large trucks barreled down the main street. “When you see Halliburton trucks running through your town,” says Robinson, “you think ‘Yeah, something’s up here.’”

Fracking: A New Vocabulary

Talking with friends in the area, Robinson learned the new regional vocabulary: “Marcellus Shale,” “natural gas harvesting,” “hydraulic fracturing” (aka “fracking”), and—most importantly—“jobs.” Friends unemployed for years spoke of their new jobs with pride. Family members and close friends were launching out and starting their own businesses to capitalize on the economic activity. But something was missing from the picture—a clear and credible assessment of the costs. Robinson decided he needed to know more.

“I started researching fracking during Lent in 2009,” he explains. “Spending an hour or two a day just reading articles, looking up information, just trying to see what was going on. To see what was happening. I used it as a spiritual discipline.”

“I started researching fracking during Lent in 2009,” he explains. “Spending an hour or two a day just reading articles, looking up information, just trying to see what was going on. To see what was happening. I used it as a spiritual discipline.”

What Robinson, a Bloomsburg University graduate well versed in the history of Pennsylvania, found didn’t surprise him. Pennsylvania has a long history of using natural resources to fuel economic growth. The nation’s first commercially drilled oil well called the Keystone State home. Williamsport became one of the most prosperous cities in the United States due to a timber boom in the late 19th century. Anthracite coal mined in Pennsylvania fueled foundries across the East Coast. Few states have a richer history of natural resource harvesting.

And very few other states have paid such a high price. Pennsylvania has the third highest number of Superfund sites, after New Jersey and California. Dangerous working conditions have taken their toll on many Pennsylvanians, and great expanses of northern Pennsylvania bear the scars of natural resource exploitation. Mountains stripped by clear-cut logging now stand hollow from mining. Rivers and streams that once teemed with life are now choked by poisonous runoff. Boomtowns have collapsed into ghost towns. Centralia, 56 miles southeast of Williamsport, is a testament to the nightmare of environmental exploitation: An abandoned town smolders from a coal mine fire that started in the 1960s and is expected to seethe for hundreds of years to come.

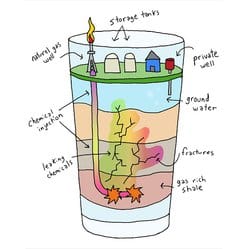

Robinson remembered all of this as he researched hydraulic fracturing. Beneath the positive stories of economic development and national energy independence, he discovered a ticking time bomb in articles about groundwater contamination, videos of flammable tap water, legal decisions preventing communities from banning hydraulic fracturing from the land miles beneath them, and data linking increases in seismic activity with the process. He felt overwhelmed. The data looked catastrophic, and people’s stories—in spite of the glow of economic opportunity—were worse.

Urging the Church to Take Action in Their Own Backyard

The 40 days of Lent came and passed, but his time in the desert motivated Robinson to begin to work for justice. He protested outside large corporate meetings. He supported friends who shut down roads to fracking wells. A large photo of him shouting at the governor of Pennsylvania appeared on the homepage of the Philadelphia Inquirer’s website.

But fighting for better stewardship of God’s creation in his backyard proved to be exhausting. Relationships became frayed with friends who were benefiting from the natural gas industry. Standing against the industry that is bankrolling the presents under the tree tends to make the Christmas holidays an awkward affair. His frequent reminders to loved ones living downstream from massive fracking operations to get their water tested irritated some folks, who stopped returning his calls.

Support from faith communities waxes and wanes. While Robinson initially had an easy time organizing friends at his church and getting individuals to show up at big protests in Philadelphia, protests fizzled after Marcellus Shale Coalition meetings concluded, and congregational participation began to fade. The same was true of many churches working for justice against hydraulic fracturing. Faith communities in the areas affected the most were not eager to take on the natural gas industry either. Many explicitly supported the development of hydraulic fracturing operations in their regions, which strikes Robinson as odd.

“In the same churches where you’ll have a lot of gas workers going, you’ll have people working to get clean water for people in places like Africa. People have gone and done service projects in areas without clean water, and they come home and say things like, ‘Oh my gosh, their water is dirty!’ You could go and talk to people in Susquehanna County and find out that it’s right here, too. It’s nuts.”

DJ and Goliath

The natural gas industry appears to be winning on the political front as well. In February of 2014, then-Governor Corbett signed an executive order overturning a moratorium on fracking in state forests and parks. Now companies with gas wells adjacent to public lands are able to leach the chemicals right from under public land, disturbing shale and leaving dangerous fluids in the ground behind. Nearly all of the 2014 gubernatorial candidates for Pennsylvania supported hydraulic fracturing in some form. It’s unlikely that substantial measures to roll back the expansion of hydraulic fracturing operations will be put into place.

There are still many loopholes and exemptions for the natural gas industry at the federal level, endangering communities around the country. It is not likely that governmental support of hydraulic fracturing will end soon. Politicians siding with the natural gas industry preach about the alleged energy security that comes from natural gas harvesting. In Washington’s current climate, it is more realistic to platform on the expansion of domestic energy harvesting rather than the curbing of energy consumption. These are hard political realities that Christian environmental stewards face. It is hard for Robinson and his Christian friends who yearn to protect God’s creation to see hope in the fight.

Robinson says he’s learned to “never give up hope” in spite of overwhelming odds. Countless stories throughout the Bible tell of good things happening in impossible circumstances. Though the odds seem insurmountable, Robinson says that plenty still fight to end fracking because “we shouldn’t want to see people, animals, and the environment devastated because of unsustainable lifestyle choices.”

In view of the cycles of boom and bust that pock Pennsylvania’s history, it is hard to envision an end to the exploitation of natural resources and to environmental degradation. Individuals who live in the communities most affected by irresponsible natural resource harvesting end up paying the price long after the money is taken out from under them. But praying and reading the Scriptures has lead Robinson to believe that a new future is possible, if Christians are willing to fight for it.

Aaron Foltz was a Sider Scholar at Palmer Theological Seminary. He lives with his wife in Philadelphia, PA.