The deaconess movement in American Protestantism emerged in the late 19th century concomitant to a dramatic increase in women’s public service opportunities, and it provided a valuable venue for women’s full-time service for God, church, and society. To become a deaconess, one completed a course consisting of training in academic subjects, including the Bible, church discipline, and church history, and in practical work, such as nursing, teaching, or evangelism. For many deaconesses, there existed an inherently reciprocal connection between evangelism and their practical work. Such was the case for Iva Durham Vennard, founder of a deaconess training school.

The deaconess movement in American Protestantism emerged in the late 19th century concomitant to a dramatic increase in women’s public service opportunities, and it provided a valuable venue for women’s full-time service for God, church, and society. To become a deaconess, one completed a course consisting of training in academic subjects, including the Bible, church discipline, and church history, and in practical work, such as nursing, teaching, or evangelism. For many deaconesses, there existed an inherently reciprocal connection between evangelism and their practical work. Such was the case for Iva Durham Vennard, founder of a deaconess training school.

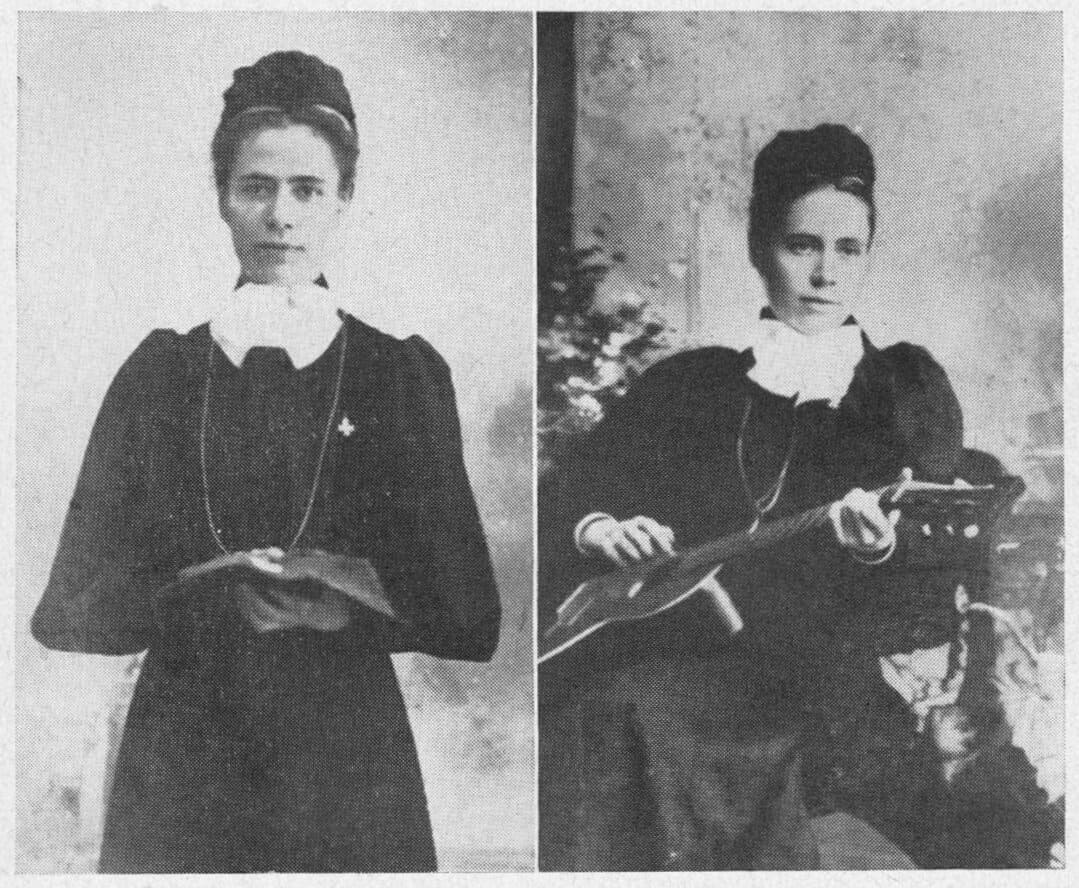

Iva Durham Vennard became a Methodist at the age of 12 when she was converted at a revival meeting. Five years later she claimed the experience of entire sanctification. After teaching for several years, she attended Wellesley College for a year and was poised to complete her college degree at Swarthmore College when her educational plans were altered at a camp meeting by a call to evangelistic work. Opportunities immediately came her way to participate in revival meetings, first as a singer, then as a preacher.

While in her early 20s, she attended a speech on deaconess work by Lucy Rider Meyer, founder of the first Methodist deaconess training school. Vennard heard something in Meyer’s words that resonated with her call to evangelistic work, and she immediately enrolled for deaconess training in the Deaconess Home in Buffalo, NY. She was soon assigned to be a deaconess evangelist, and in this capacity she held revival meetings in churches throughout the state of New York.

After several years as a deaconess evangelist, in 1902 she founded Epworth Evangelistic Institute, a deaconess training school in St. Louis. As its name suggested, her school was characterized by its intent to train deaconesses in evangelism. “Real, genuine, soul-saving work,” she once wrote, “is the fundamental mission of all deaconess work, and no deaconess measures up to her privilege in service or fulfills her responsibility toward God who does not aim persistently at the definite regeneration of her people.”

While Vennard cared passionately for evangelism, she brought similar zeal to humanitarianism, which she believed encompassed three areas: industrial, medical, and educational.

While Vennard cared passionately for evangelism and devoted her life to training students in its practice, she brought similar zeal to humanitarianism, which she understood as attending to temporal benefits such as better living conditions and social improvements. Humanitarianism, she believed, encompassed three areas: industrial, medical, and educational. For that reason, students at Epworth were trained in settlement work, nursing and hygiene, and industrial training. Their curriculum in these areas was complemented by practical experience, which was readily at hand since Vennard purposely chose to situate Epworth in a notorious tenement district called Kerry Patch.

The deaconess work sponsored by Epworth in Kerry Patch included a combination of evangelism and humanitarianism. Deaconesses visited in homes, jails, the juvenile court, and in the red light district. They ran a travelers’ aid ministry to care for runaway children and unprotected girls. They also provided nursing care in homes and city hospitals, pursued evangelistic work in city missions, and staffed the Epworth Emergency Home, where girls considered incorrigible by the juvenile court were sheltered. In addition, some deaconesses lived in Epworth Settlement, an outreach house that offered programs for the community, such as a Sunday school, kindergarten, sewing school, girls’ and boys’ clubs, a library, and a thrift fund.

In the following quote, an Epworth graduate articulates what she received from her deaconess training, namely that, while evangelism was the priority for a deaconess, practical work to relieve suffering and misery was inextricably linked to it:

Every true deaconess first of all is an evangelist, she is a soul winner; but a very intimate relation exists between the souls and bodies of mortal beings so many times the heart has been captured for Christ by relieving bodily distress. We find our pattern in the example of our Savior Who, while he pitied the suffering body, pitied the sin-sick soul more, and we hear Him not only say take up thy bed and walk, but thy sins which were many are all forgiven. Every field thus far opened up to the deaconess offers peculiar advantages for transforming the lives of those with whom she comes in touch. (A. Combs, “The Deaconess as a Social Worker,” 1909)

After nearly a decade as principal of Epworth, Vennard moved to Chicago and in 1910 founded Chicago Evangelistic Institute, where she continued her holistic training in evangelism and practical work for women and men who intended to be ministers, evangelists, and missionaries. Shortly after her death, the school was relocated to rural Iowa and renamed Vennard College, after its founder.

Priscilla Pope-Levison is professor of theology and assistant director of women’s studies at Seattle Pacific University and author of Turn the Pulpit Loose: Two Centuries of American Women Evangelists (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).