The Department of Justice (DOJ) announced on August 18, 2016 that it will no longer outsource federal prisons to private prison companies, because many of these privately operated prisons have failed to provide adequate mental health and medical attention to their detainees. In an effort to increase profits, the managers of these prisons have been found to cut corners, resulting in appalling living conditions for inmates.

Yet according to the Huffington Post, “The Department of Justice announcement … only applies to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, which accounts for just a fraction of the private prison industry’s business.” While 13 federal prisons will be affected by this decision, the bulk of federal prisons operated by for-profit companies are sourced out by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is another federal law enforcement agency that outsources its needs to private prison companies.

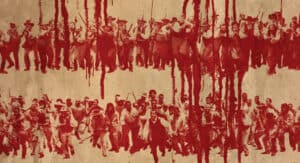

Following the August 18th announcement, the two private prison powerhouses, GEO Group and Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) saw major dips in the stock market, but this blow is far from fatal. Just hours after President-elect Donald Trump won the presidential nomination, stock prices for both private prison companies surged upward. These two prison corporations have a combined revenue of 3.3 billion dollars and have fueled the surge in the nation’s incarceration rates, with the prison population more than doubling in the last 16 years and showing no sign of slowing down. Since 1989, GEO and CCA have also spent over $35 million in lobbying and political campaigns, effectively keeping African Americans and other minorities oppressed in a disadvantaged criminal justice system. This is done by lobbying for three-strike laws, racial profiling, and the war on drugs. With the three-strike laws and the war on drugs, minor offenses that would usually call for a slap on the wrist ends up costing the offender several years in prison and a record once they are released. Racial profiling, whether done intentionally or not, puts African Americans at a disadvantage simply because of the color of their skin and leads to a disparity in arrests and convictions. With these types of laws in place, it is no surprise that the ratio of African Americans in prison compared to whites is 7:1. Also, while the United States makes up only 5% of the world’s population, it houses 25% of the world’s prisoners. One factor driving these numbers is private companies profiting from—and therefore lobbying for an endless supply of—incarcerated individuals.

These two prison corporations have a combined revenue of 3.3 billion dollars and have fueled the surge in the nation’s incarceration rates, with the prison population more than doubling in the last 16 years and showing no sign of slowing down.

In order to turn this trend around, the Department of Homeland Security, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, must follow the Department of Justice’s lead and acknowledge the negative effect that prison privatization has on the incarcerated as well as on society as a whole. Not only will these federal agencies need to stop outsourcing to these companies, but the business practices of these for-profit companies also need to be brought into the light. Within the last few years, both companies have diversified their services to fill the needs of behavioral interventions and electronic monitoring equipment. As these companies continue to expand their services, it becomes harder to tackle these injustices. When CCA addressed its idea to keep revenue flowing into its company in an annual report, it also indirectly exposed its Achilles’ heel in the following statement:

The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices or through the decriminalization of certain activities that are currently proscribed by our criminal laws. For instance, any changes with respect to drugs and controlled substances or illegal immigration could affect the number of persons arrested, convicted, and sentenced, thereby potentially reducing demand for correctional facilities to house them. … Legislation has been proposed in numerous jurisdictions that could lower minimum sentences for some non-violent crimes and make more inmates eligible for early release based on good behavior.

Exposing prison powerhouses is an uphill battle, given the number of lobbyists and ample funds at their disposal, but even the slightest bit of progress combating injustice can gain momentum. For this reason, we invite you to play a role by signing this petition demanding that the Department of Homeland Security end its contracts with all private prison companies.

Merrick Korach is a student pursuing the Masters of Divinity and Masters in Business Administration: Economic Development dual degree. He aspires to bring the holistic healing of the Gospel to the world we live in through business, education, and politics. His hope is that through a transformative interaction with the Gospel, hearts will be made new and hopeful change will take place.

Resources

- Anderson, Lucas. “Kicking the National Habit: The Legal and Policy Arguments for Abolishing Private Prison Contracts.” Public Contract Law Journal 39 no. 1: 113-139. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed January 11, 2017).

- Butler, Paul. “One Hundred Years of Race and Crime.” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-) 100, no. 3 (2010): 1043-060. http://ezproxy.eastern.edu:2076/stable/25766114.