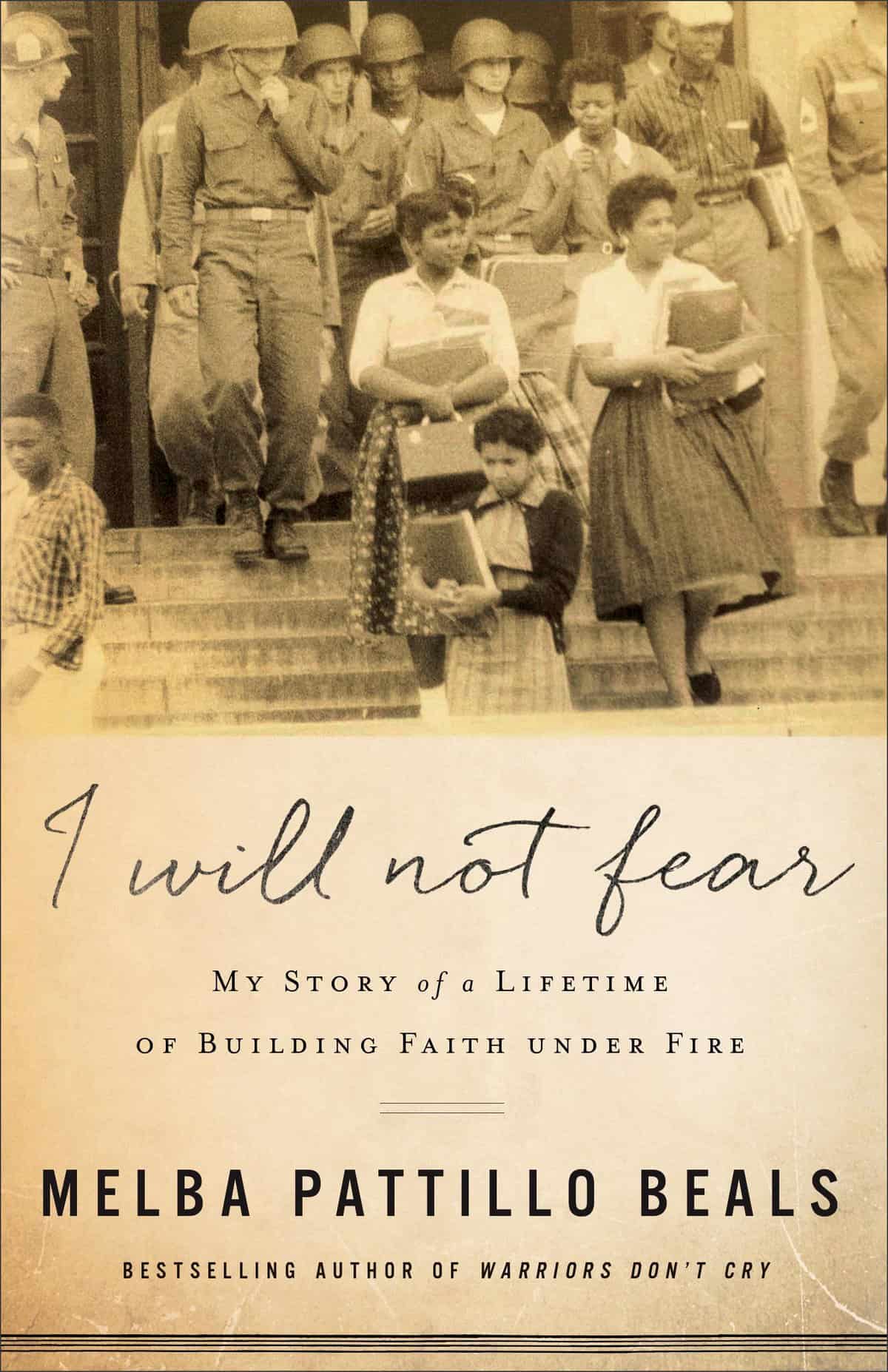

Melba Pattillo Beals was one of nine African American students chosen to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. Anyone who has seen photos or television footage of the Little Rock Nine surrounded by faces distorted with rage will never forget the disturbing images. The courageous teenagers endured shouting, rock-throwing mobs and death threats, and were terrorized by the KKK. Although US Army troops mobilized to escort them into the school and serve as bodyguards, they could not protect the teens from violent attacks and humiliations perpetuated by white students. Faith and family equipped Melba, at the tender age of 15, to stand up to hatred and racial prejudice.

I was determined to remain a Central High student to complete my task of integration. I focused on putting as much of my energy as possible into coping mechanisms for surviving the abuse of each day. Faith, trust, and hope became the reasons I could get up, get dressed, and return to school each day for a day of misery.

I felt the emergence of my warrior, the inner voice that energized me and affirmed that I was doing God’s work amid the harsh name-calling and frequent blows. The most frightening time was when I needed to use the girls’ room. Sitting in the cubicle, I was trapped. Some of the girls held the door closed. Then they stood on the toilet seats and threw bits of lighted notebook paper in on me. At first, I was frozen, sitting there wanting to cry and call for help. But there was no human help; my only help would come from God. I dug deep inside to find my well of energy and answers to get past the self-pity and turn it into action. I realized that God would rescue me, but I must act. I could not simply sit down and cry. I had to get past the fire and smoke that covered me. I had to put fear in its place. I returned the fire by throwing the paper back on my attackers.

I felt the emergence of my warrior, the inner voice that energized me and affirmed that I was doing God’s work amid the harsh name-calling and frequent blows.

Over and over again, Grandmother would remind me that I was one with God and part of His infinite plan. She promised that when I understood that concept, I would realize my own value. I would know for certain I was equal, no matter what other people thought.

Meanwhile, I had to face the fact that I was surrounded by hostility, even in my own community. White supremacists were pressuring our people to insist we nine give up. African Americans did not fully realize what they stood to lose in the future if we gave up—future rights to better education and better jobs.

People in my own church began asking me, “Why go where you’re not welcome?” Stunned by the question, I would stop to ponder. Finally, I remembered the answer Grandmother had given me long ago when we both were listening on the radio to Jackie Robinson taking his place as the first African American to play in major league baseball. People booed and asked Grandma why he wanted to be there where he was unwelcome. She replied, “If you go only where you are welcome, that’s where other people want you to go, not where you choose to go. You’re limited by their vision—not living your own dreams.”

Now I was going where I was not welcome. When I spoke to Grandma about it, she said, “No one has the right to keep any institution we pay for with our own tax money from you. Central High is your school as much as theirs. Both your parents pay taxes.”

If you go only where you are welcome, that’s where other people want you to go, not where you choose to go. You’re limited by their vision—not living your own dreams.

For every insulting name I was called, I repeated the 23rd Psalm and spoke five positive compliments to myself. I discovered that the notion of self-talk requires surrender to the idea that God is a just God and that, inevitably, you will receive the very reward you seek or one even better than you might be striving for. Patience is the answer. I was learning to “wait on the Lord.”

I sustained an inhuman number of mental and physical injuries from bullies surrounding me. Time after time, I reached for the inner voice that comforted me: If I surrender to bullying torture, then they will use it as a tool against me and my community over and over again to hold on to their traditions of prejudice. They will deny me the vote, education, jobs, or housing. I will overcome their efforts by not falling victim to bullying. At that point, my warrior roared inside. I felt totally determined to remain in Central High. It was my place as much as it was theirs. God had called me to this task to be present at Central High for a reason, and I could not give up.

As I grew older and witnessed the toppling of the walls of segregation at Little Rock and schools across the South, I began to understand the impact of my decision to remain at Central High. Just as Dr. King had said, integrating Central wasn’t all about me. It was about the opportunities future generations could claim based on my job. As Grandmother had said, “It was God’s assignment.” I became more and more grateful for not only my growing faith in God but also my trust that He would see me through all the challenges of my life, as He did that year in Central High.

Melba Pattillo Beals is a recipient of this country’s highest honor, the Congressional Gold Medal, for her role, as a fifteen-year-old, in the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. A retired university professor with a doctorate in International Multicultural Education, she is a former KQED television broadcaster, NBC television news reporter, ABC radio talk show host, and writer for various magazines, including Family Circle and People. Beals’s book Warriors Don’t Cry has been in print for more than twenty years, has sold more than one million copies, and was the winner of the American Library Association Award, the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, and the American Booksellers’ Association Award. She lives in San Francisco and is the mother of three adult children. This excerpt is taken from I Will Not Fear: My Story of a Lifetime of Building Faith under Fire by Melba Pattillo Beals, published by Revell, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2018. Used by permission.