The calling of the faithful is clear: feed the hungry and you will live.

For the past twenty years, I have traveled the United States and other parts of the world observing, researching, and addressing hunger and poverty. Much of what I have learned about addressing hunger and poverty is similar to what I learned by working in disaster response. The problem is often overwhelming, and we need to find a way to work together in a coordinated response to address these issues that have been around for thousands of years.

Years after Hurricanes Katrina, Gustav, and Ike, while living and working in San Antonio, I was offered the opportunity to put these ideas to the test when I was asked by Texas Baptists to start an organization focused specifically on coordinating a collective response to hunger, the Texas Hunger Initiative (THI). The premise was that hunger and poverty are too large and too complex to address alone. We would all need to work together in a coordinated capacity if we wanted to make a dent in them, much less end them.

We also knew that we had a cultural problem. Our nation tends toward blaming the hungry and poor for their plight rather than walking alongside them to find solutions. Blaming the poor for their poverty only adds insult to injury and is largely an inaccurate diagnosis.

We also had a spiritual problem. Jesus spoke frequently about loving our neighbor in practical and tangible ways, such as providing food for the hungry, but hunger in Texas was more prevalent than in almost any other state in the nation or in any developed country around the world. We needed a stronger understanding of our collective call to love God and our neighbor, and we needed to move with a sense of urgency, as I would soon learn.

As I was transitioning into this new position, I was told I needed to meet Pastor Dan Trevino, because his congregation was providing food for the hungry. Dan’s congregation was on the South Side of San Antonio, a sister neighborhood to the West Side, where I was living. Dan spoke to me about his congregation’s ministries in the community. They had a charter school that used the church’s education building, a food pantry, a community garden, and literacy and employment classes. If you can think of an idea for ministry, Dan and his church were

probably doing it.

As we talked and toured the church, Dan told me about a formative experience. He said that he and his sons had come to the church one Saturday morning before dawn to make breakfast tacos for the elders in the congregation. When they pulled into the church parking lot, the headlights of his van revealed children in the church’s dumpster. He and his sons were startled, and so were the children in the dumpster. The kids tried to get out of the dumpster and run away, but Dan was able to get to them and calm their fears.

Dan invited the kids into the church’s kitchen and made them breakfast tacos before the elders arrived. Once they were full, he began to ask them why they were in the dumpster. Slowly, the boys began to open up and told him that they did not have any food in the house, so they had snuck out while it was still dark to rummage through the dumpster to see if they could find something to eat.

I was stunned. Dan’s church wasn’t far from the Riverwalk and all that we enjoy visiting in San Antonio. Yet there were children in his community so impoverished that they were rummaging through a dumpster to find food. This was a story I expected to hear about the developing world, but downtown San Antonio? My shock led to dismay. How could our nation passively let children experience such extreme circumstances? How could the church?

Gandhi called poverty the harshest form of violence. I believe hunger is the harshest form of poverty. Hunger is debilitating. It stimulates physical pain, anger, lethargy, and depression. It will keep you up at night and ironically cause drowsiness during the day. I can only imagine the shame and humiliation parents experience when their children miss meals. One of our primary responsibilities is to provide a stable household for our families. We want to make sure they have food, a consistent place to sleep, and a loving environment. If we were unable to provide them with three meals a day and a place to sleep, we would probably feel inadequate and ashamed.

These dumpster-diving kids were no different than the hurricane survivors on the bridge: they had been stranded by tragedy.

Travel to any urban or rural impoverished community and you will find similar stories everywhere. Today in the United States, over forty million Americans are food insecure (or at risk of hunger). According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), this means that at times during the year, these individuals live in households that are uncertain of having or are unable to acquire enough food to meet the needs of all their family members, because they have insufficient money or other resources for food. Nearly one out of six children in the US live in a food-insecure household. That number is one out of two in south Texas.

Nearly one out of six children in the US live in a food-insecure household. That number is one out of two in south Texas.

Furthermore, economic inequality is the worst it has been in modern American history. A person working a full-time job and getting paid minimum wage earns less than the federal poverty line, and the poverty line itself is an inaccurate underrepresentation of true poverty.

Most Christians are probably familiar with Jesus’s teaching in Matthew 25: “For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me” (vv. 35–36). This is the only apocalyptic (or end-of-the-world) scene in Matthew. Jesus the King has returned, and he is sitting on the throne. This is the final judgment. All people are gathered, and Jesus is separating them—the sheep and the goats, the righteous from the accused.

To the astonishment of the people gathered, “the criterion for judgment is not confession of faith in Christ. Nothing is said of grace, justification, or the forgiveness of sins.” Instead, what matters is whether a person has acted with

love and cared for the needy. These acts are not just extra credit but “constitute the decisive criterion for judgment.” Essentially, “when the people respond or fail to respond to human need, they are in fact responding, or failing to respond, to Christ” (M. Eugene Boring, The Gospel of Matthew.)

The calling of the faithful is clear: feed the hungry and you will live.

A hurricane we can understand. But poverty? Hunger? Many of us believe people just need to get a job and quit complaining. Unfortunately, this type of narrow thinking has only worsened our current situation.

But we don’t rush to rescue these sufferers the way we did when Katrina wreaked its havoc. A hurricane we can understand. But poverty? Hunger? Many of us believe people just need to get a job and quit complaining. Unfortunately, this type of narrow thinking has only worsened our current situation. People experience hunger in our nation typically because they live in poverty. They are therefore forced to decide between purchasing food or medicine, paying for housing or making a car payment, and so on. The truth is that the realities of hunger and poverty are complex.

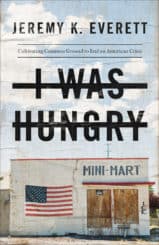

Jeremy K. Everett (MDiv, Baylor University) is the founder and executive director of the Texas Hunger Initiative, an organization that partners with the United States Department of Agriculture, Texas state agencies, the corporate sector, and thousands of faith- and community-based organizations to develop and implement strategies to alleviate hunger through policy, education, research, and community organizing. A noted advocate for the hungry, he served on the National Commission on Hunger, has spent over two decades ministering to the poor, and frequently speaks on poverty, hunger, community development, and social entrepreneurship. Everett regularly writes for HuffPost and has been featured in PBS documentaries, in newspapers such as the Dallas Morning News, and on talk shows. Excerpt taken from I Was Hungry by Jeremy Everett, ©2019. Used by permission of Baker Publishing.

Jeremy K. Everett (MDiv, Baylor University) is the founder and executive director of the Texas Hunger Initiative, an organization that partners with the United States Department of Agriculture, Texas state agencies, the corporate sector, and thousands of faith- and community-based organizations to develop and implement strategies to alleviate hunger through policy, education, research, and community organizing. A noted advocate for the hungry, he served on the National Commission on Hunger, has spent over two decades ministering to the poor, and frequently speaks on poverty, hunger, community development, and social entrepreneurship. Everett regularly writes for HuffPost and has been featured in PBS documentaries, in newspapers such as the Dallas Morning News, and on talk shows. Excerpt taken from I Was Hungry by Jeremy Everett, ©2019. Used by permission of Baker Publishing.